We need to talk about Network.

In service of an obligatory locked-down family movie night this past weekend, I decided to dust off the archives and select a film I had watched since my early college days. On first viewing almost five years ago, I knew that this 1976 film was great and spoke to the initial preconceptions I had commencing my studies to become a journalist. Now, sitting down to watch it again, I find myself appreciating it for another aspect, one that I feel has gone unreported. But first, for the viewing-deprived, a quick rundown of the flick.

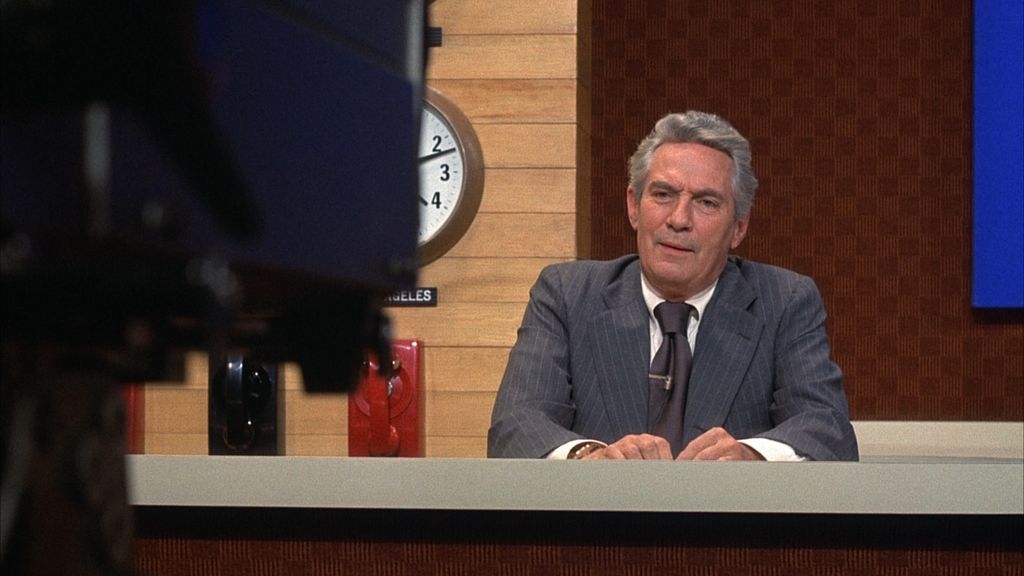

Network commences with news anchor Howard Beale and his boss Max Schumacher, played by Peter Finch and William Holden respectively, drunk off their asses following Beale’s booting from the UBS newsdesk. Beale proceeds to go off live on air, first by declaring to commit suicide during prime time and then by claiming to have had psychic premonitions denouncing the American status quo. This result is one of the greatest line reads in film history:

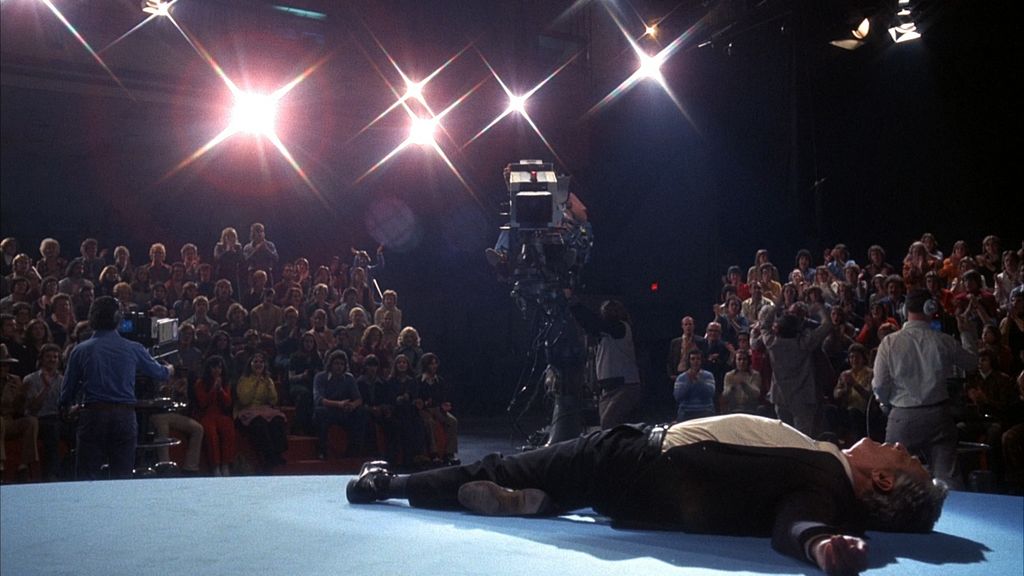

Programming executive Diana Christensen (flawlessly played by Faye Dunaway) sees an opportunity in Beale’s blustering to reshape the news hour, showcasing him as “an angry prophet denouncing the hypocrisies of our time”. Backed by company executive Frank Hackett (Robert Duvall), Christensen succeeds in her plans only to have them later backfire spectacularly when Beale turns his attention to hypocrisies perpetuated by the corporate cavalry backing him.

Firstly and without contention, Network is a fabulous film. Though it is usually lost in director Sidney Lumet’s filmography, writer Paddy Chayefsky’s take on a news anchor and station infected with prophetical sensationalism fueled by corporate greed is hilarious, relevant and brilliantly executed. One that Chayefsky was rewarded for with an Oscar for Best Original Screenplay.The film also gave Oscars to Finch (posthumously) and Dunaway, as well as Best Supporting Actress for Beatrice Straight (fun fact, Straight’s performance lasted only five minutes and two seconds, the shortest to ever win an Oscar), the tallied wins out of ten nominations the film received.

However, though relevant, the film has dated. Not only was the sub-industry of broadcast news reporting revolutionised by the introduction of dedicated news channels (CNN was launched in 1980) and thereby creating a scenario for it to actually generate a profit for itself, but the modern age of social media and the commodification of information has shattered then-ideas about the disconnect between editorial decisions and corporate interference. Said disconnect may have already been coming under fire back in 1976, but not to the capital proportions of today, and not in the way how it now impacts content.

There is a lot to like about Network, but I contest that its attempts to highlight the absurdity of the haunted fishbowl and what we end up watching on it is not the only strength it has. There is a methodology behind its storytelling that is ever present throughout the film but is handled so expertly that it avoids subjection to bad-faith scrutiny. To that end, I propose the following.

Network is the first mainstream instance of pop culture metatextuality.

For those unsure of the terminology, metatextuality is when a piece of text i.e. a book, movie, whatever takes a critical or commentary dig at another piece of text. It resides under the conceptual umbrella of transtextuality, which describes the phenomenon of text changing according to its relationship with other text.

Metatextuality has now become a buzzword in contemporary pop culture discourse with its wide application resulting in the term becoming bastardised, even ubiquitous. It’s a situation not just permeated by internet hot takes (wink). Disney has done gangbusters with its live-action remakes being meta, while the Dan Harmons and Charlie Brookers are happy to exploit the device on television in order to declare the world is awful and its people terrible. You get good meta and you get bad meta, and we’ve become much more accepting of bad meta in our popular media.

In 1976, The meta that Network dealt in was very fresh. It was a project of theatrical scale that took on the formulaic nature of television, highlighting the decision making and announcing business’s disposition to broadcast absolutely anything so long as it makes money. If the film is anything, it’s a predecessor and more sophisticated take on the ideas Richard O’Brien was exploring in his follow-up to The Rocky Horror Picture Show, 1981’s Shock Treatment. O’Brien took the exaggerated approach and came pretty close to predicting the rise of reality television, and to what lengths people will be exploited in the name of entertainment. In his 2000 re-review of Network, critic Roger Ebert doubled down on that sentiment and declared the film prophetic, signaling the rise of the likes of Jerry Springer and the World Wrestling Foundation.

Meanwhile, Chayefsky, focusing on the essential service of news reporting, ate his own tail and deployed the TV tropes and predictable formulas that he sought out to spotlight. Take for instance the B-plot of the film. William Holden’s character engages in a sexual relationship with Dunaway. The relationship, much to his disappointment, is effectively devoid of romance with Dunaway completely wrapped up in her work to the point that their foreplay is driven by her ambition to become the most powerful woman in broadcast television (a not-at-all impossible possibility, what with this character’s arc). Nothing that hasn’t been seen in your daily soap opera or Friday night movie of the week. To round off, both Network and Shock Treatment treat the complacency of the TV audience to ingest any kind of content as a given, which is not much of a mind stretch.

But here’s where Chayefsky takes the cake. Not only is Network using metatextuality as an active plot characteristic, but the text of which it is being critical of (brutally so, if you watch the film) is itself. The film dedicates entire scenes where characters break down the formulaic nature of the plot that concerns them, specifically that which revolves around Holden and Dunaway’s relationship. Hell, Holden’s presence in the second half of the film is solely to play out the cliche breakup between the old-school has-been and the ambitious though flawed executive. The performance is one big shrug to the audience. This is on top of other plot points such as Howard Beale coming full circle that he has heard the voice of God, first via actual visions and then in the form of his ominous corporate overlord, Mr Jensen.

In a time of over-saturated content hailed for doing the barest minimum of critical self-oversight, Network proves that a piece of big-budget media can turn take the zeitgeist on and turn it on itself, while also not deeming itself superior to it. This, despite it having every right to deem itself so. Yes, the subplots of the film were a response to then issues of the time (bolstered by Lumet’s precedence as an auteur of old New York City), but that doesn’t distract from its message or actively calls them out to the point that it could be accused of politics. No film made today making these kinds of storytelling decisions would enjoy the level of critical praise that this film received in 1976.

Network is a masterful stroke of meta and it doesn’t get enough praise for that, and it was a great pick for movie night to boot.