The cruel irony of South Africa’s essential workforce isn’t their dedication — it’s that they barely afford to show up for the jobs they love. New research reveals that nearly half of the country’s deskless workers, who make up 75% of the workforce, routinely exhaust their wages before their next payday, perpetuating a cycle of debt that threatens the backbone of Africa’s most industrialised economy.

The 2024 Deskless Worker Pulse report, surveying 1,600 frontline workers, exposes a paradox: 98% of these workers express genuine satisfaction with their jobs, yet their average monthly earnings of R5,000 to R10,000 (roughly $260 to $520) barely cover basic necessities. Many begin their workday at 3 a.m., not from choice but necessity — navigating a labyrinth of unreliable public transport that can make or break their employment.

“These are essential workers who often operate under challenging conditions,” explains Nonsuku Mthimkhulu, Head of Customer at Jem, the HR platform behind the research. But ‘challenging’ barely scratches the surface. For these workers, each day is a careful orchestration of timing and finance, where a missed taxi can mean a missed shift, and a missed shift can mean no money for tomorrow’s taxi.

The mathematics of survival is stark: 97% of those who run out of money before payday need it for essentials, not luxuries. Forty-four percent have no emergency savings whatsoever. It’s a precarious existence where financial stability remains perpetually out of reach, forcing many into the arms of loan sharks and payday lenders—a decision that often proves financially fatal.

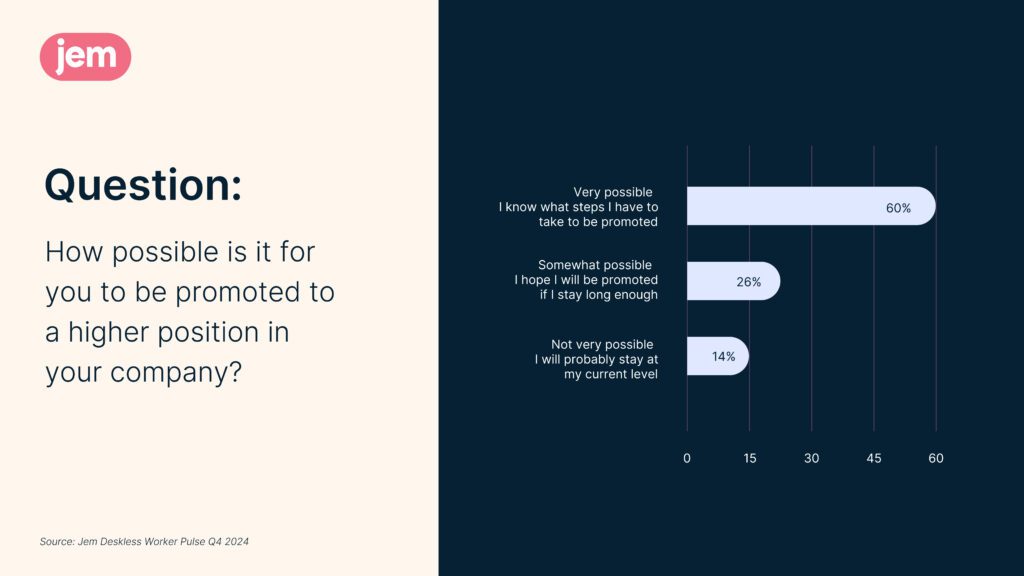

What makes this situation particularly poignant is the workforce’s resilience and optimism. Despite the daily gauntlet of challenges, these workers find profound meaning in their roles. After wages, opportunities for promotion and believing their work is meaningful are their strongest motivators. Most say there are promotion opportunities, and 60% claim they know what to do to be promoted. Yet more than half report feeling appreciated only rarely — a disconnect between institutional recognition and personal pride that characterises much of South Africa’s labor landscape.

The transport challenge exemplifies the broader systemic issues at play. As Caroline van der Merwe, co-founder and Chief Product Officer at Jem, explains, “Many people we spoke to said their routes and transport changes whether they are coming or going to work, because different drop-offs are dangerous at certain times.” This isn’t merely about logistics; it’s about survival in a system where the basic ability to reach one’s workplace becomes a daily act of courage and resourcefulness.

Some employers are attempting to address these challenges through innovative solutions like Earned Wage Access (EWA), which allows workers to access their already-earned wages before payday. The impact has been significant: over 70% of workers with EWA access report no longer needing predatory loans. But such solutions, while meaningful, highlight a deeper question: In an economy dependent on essential workers, why must they struggle so fundamentally just to maintain their essential roles?

The resilience of South Africa’s deskless workforce — their ability to find meaning and satisfaction in their work despite overwhelming obstacles—speaks to a deeper truth about human dignity and the nature of work itself. But it also raises uncomfortable questions about the sustainability of an economic system that relies so heavily on workers who can barely afford to participate in it.

As Simon Ellis, co-founder and CEO of Jem, notes, “Many simply don’t make enough money to get through the month.” This statement, in its stark simplicity, encapsulates both the problem and the challenge facing South African society: How to bridge the gap between the essential nature of these workers’ contributions and their ability to sustain themselves while making them.

The 2024 Deskless Worker Pulse doesn’t just present data; it holds up a mirror to South Africa’s economic contradictions. In a country still grappling with the legacy of inequality, the daily struggles of its essential workforce suggest that the path to economic justice remains long and complex. Yet the very existence of this workforce — resilient, proud, and overwhelmingly engaged despite their challenges — offers hope that solutions are possible, if society chooses to pursue them.