A few weeks ago, a friend told me a story that has stayed with me longer than I expected. It wasn’t the kind of dramatic anecdote we usually think of when talking about technology’s impact — no cybercrime, no billion-dollar startups, no dystopian collapse. It was quieter.

It was about his mother’s friend. She needed a new phone. Nothing complicated. She didn’t want to scroll TikTok or video-call five people at once. She only wanted to call, text, and send the occasional WhatsApp message to her family and friends. That was it.

My friend found an old Nokia feature phone running KaiOS — one of the so-called “smart” feature phones that had seemed, briefly, like a bridge between two worlds. Calls, SMS, WhatsApp. Simple. Familiar.

The mobile network helped swap her old micro SIM for a nano SIM. Everything was set up, eventually. But by the time they were ready, they discovered WhatsApp no longer supported her device. An app that had become, for her, a lifeline to family and friends, was now simply inaccessible. The bridge had quietly collapsed.

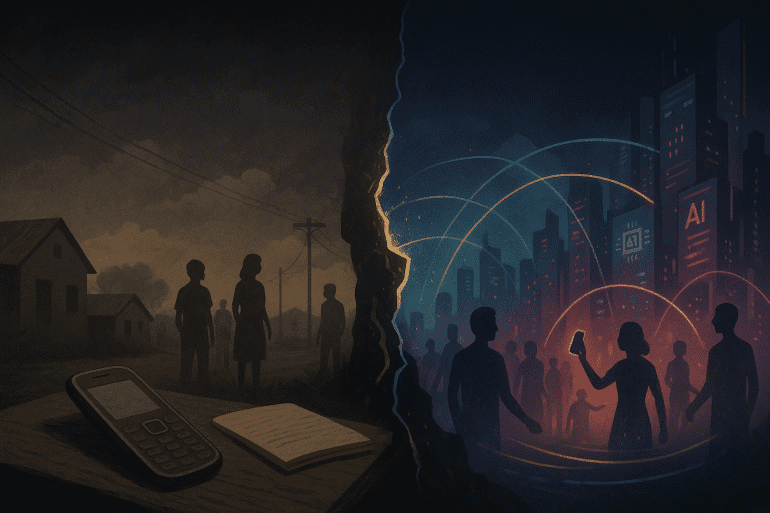

It’s a small story. Perhaps even an inevitable one. But it reveals something disquieting when you sit with it long enough: a sense that the very people who most need stability — the elderly, the differently abled, the rural and marginalised — are often the first to be abandoned by the forward march of technology.

Who, exactly, is it convenient for?

In theory, we have never had it easier. Services are digitised, automated, optimised. But “ease” is a slippery word. Convenience often isn’t about making life easier for everyone. It’s about making life cheaper, faster, more profitable for those at the top of the chain. And those who fall outside the narrow profile of “the ideal user” — young, urban, digitally fluent, permanently online — are left to scramble for workarounds.

You don’t have to dig far to see this playing out. According to Pew Research, the new “normal” post-2025 is predicted to be “far more tech-driven,” but alongside the promises of better efficiency and broader access, experts warn of widening gaps: between urban and rural, young and old, wealthy and struggling. The McKinsey Technology Council, too, in its top trends in tech, notes the accelerating pace of innovation — but rarely pauses to ask who struggles to keep up.

The gap isn’t just economic. It’s emotional. Psychological. A growing sense, voiced quietly in conversations and forums and call-in shows, that technology isn’t something we adopt but something that happens to us. That if you stop moving — even for a year, a month — you might not find your way back.

Profit or empowerment?

We’re sold a particular mythology of innovation: that every new wave of technology lifts all boats, that disruption is ultimately good, that obsolescence is just the cost of progress. But who decides what progress looks like?

In 2025, despite all the promises, 5G has not revolutionised everyday life in the way it was marketed to. Coverage remains patchy. Speed differences, outside major metros, are marginal for most users. Yet the need to buy 5G-capable devices, to stay “current,” has been baked into the upgrade cycle. The cost, financial and environmental, is quietly passed down to consumers.

It’s a pattern repeating now with AI. The noise is deafening. Every sector — especially creative industries — is being “disrupted”. Jobs are shifting or disappearing. Tools are proliferating faster than anyone can track. AI is pitched as the great equaliser, yet those without access to powerful devices, high-speed connectivity, and specialised digital literacy are once again left behind.

Data from Experian shows that even as digital services expand, around 75 million people globally are still “being left behind” in the tech revolution. In South Africa, the State of the ICT Sector Report (ICASA, 2025) reveals that while smartphone penetration is growing, it remains far from universal. And beneath the surface, issues like digital literacy, affordability, and infrastructural inequality tell a more complicated story.

The myth of choice

Black Mirror’s “Common People” episode imagined a world where life itself was a series of mandatory subscriptions. Watching it, it was hard not to flinch. The fiction wasn’t that distant from reality. The illusion of choice in tech is just that: an illusion.

Yes, you can choose not to use the major monopolistic platforms — in theory. But the alternatives are often clunky, obscure, less reliable. They require more technical skill. They don’t integrate seamlessly into the systems our work and social lives increasingly depend on.

Meanwhile, convenience is marketed as the ultimate luxury. The value proposition isn’t “this will free your time for what matters” — it’s “this will ensure you won’t be left behind.”

When opting out isn’t really an option

Even when alternatives are available, take-up is sparse. We often think, surely there are others like me who want smaller, simpler devices. More ethical platforms. Less intrusive technology. But when the market responds, uptake is often low.

It’s easy to overestimate how representative our circles are. Echo chambers, even offline ones, trick us into thinking there’s a bigger movement than there is. When it comes time to “vote with your wallet,” inertia often wins. Convenience wins. Marketing wins.

Take the iPhone Mini for example, beloved by tech critics and a vocal minority of users, was ultimately a commercial failure. Apple cancelled it after disappointing sales. A stark reminder that big talk about wanting alternatives doesn’t always translate into mass behaviour.

Invisible biases, invisible exclusions

It would be comforting to think this is purely about money. That if enough demand existed, companies would meet it. But there’s a deeper layer: who gets considered in the design process.

For too long, the “average user” has been imagined as young, able-bodied, urban, and Western. Biases in AI models are well-documented — models trained on data that excludes, marginalises, or caricatures whole segments of the human experience.

Hardware design follows the same patterns. Devices are made thinner, smaller, sleeker — and harder to hold for people with motor impairments. Interfaces are optimised for eyes that aren’t ageing. Updates assume a baseline of digital fluency that isn’t universal.

Reports like those from the UNDP and World Economic Forum call for more “inclusive tech,” but the urgency often feels abstract. Meanwhile, those struggling are left to patch together solutions on their own. An extra app to make text bigger. A clunky workaround to keep an old service alive. The mental load quietly rises.

Who is innovation for?

I don’t expect companies to turn into charity organisations. They exist to make profit. That isn’t new. But if we’re going to keep punting innovation as an unequivocal good, we should ask harder questions.

Good for whom?

The small story of my friend’s mother’s friend may seem trivial. In the sweep of things, one woman losing WhatsApp access doesn’t register on corporate earnings calls. But it’s not about the one case. It’s about the pattern it belongs to. The creeping sense that as we digitise more and more of life, those who aren’t “ideal users” are treated as expendable.

And when DEI initiatives — already fragile — are quietly shelved under the rhetoric of “efficiency” or “post-woke” fatigue, it’s hard to see how this will reverse.

Sitting with the discomfort

There’s no neat ending here. No grand call to action. The reality is messier than that.

Most of us, even when uneasy, are complicit. We accept the latest updates. We buy the new models. We adjust to the new normal, then the next one.

But perhaps it’s worth lingering, however briefly, with the stories that don’t make the headlines. With the woman who simply wanted to send a WhatsApp. With the invisible mental load carried by those trying to navigate interfaces not built for them. With the possibility that “progress,” when unexamined, can leave just as many behind as it claims to uplift.

Perhaps it’s enough, for now, to resist the temptation to tie a bow around it. To stay uneasy. To notice who is missing from the future we’re rushing to build, because when people are left behind quietly enough, for long enough, we begin to forget they were ever meant to be included at all.