The largest outages of 2025 weren’t edge cases or freak technical events. They were stress fractures running through the core of the modern internet, briefly visible when millions of users tried to log in, load pages, or simply get work done and couldn’t.

Using Downdetector data from across the year, Ookla analysed millions of user reports to identify the biggest website and service outages globally and by region. The resulting picture, detailed in its analysis of the largest outages of 2025, is less about momentary failure and more about how concentrated digital infrastructure has become.

Outages are often framed as a temporary inconvenience. Refresh the page, wait it out, move on. What this data shows instead is how deeply interconnected today’s services are, and how quickly a problem in one layer becomes everyone’s problem.

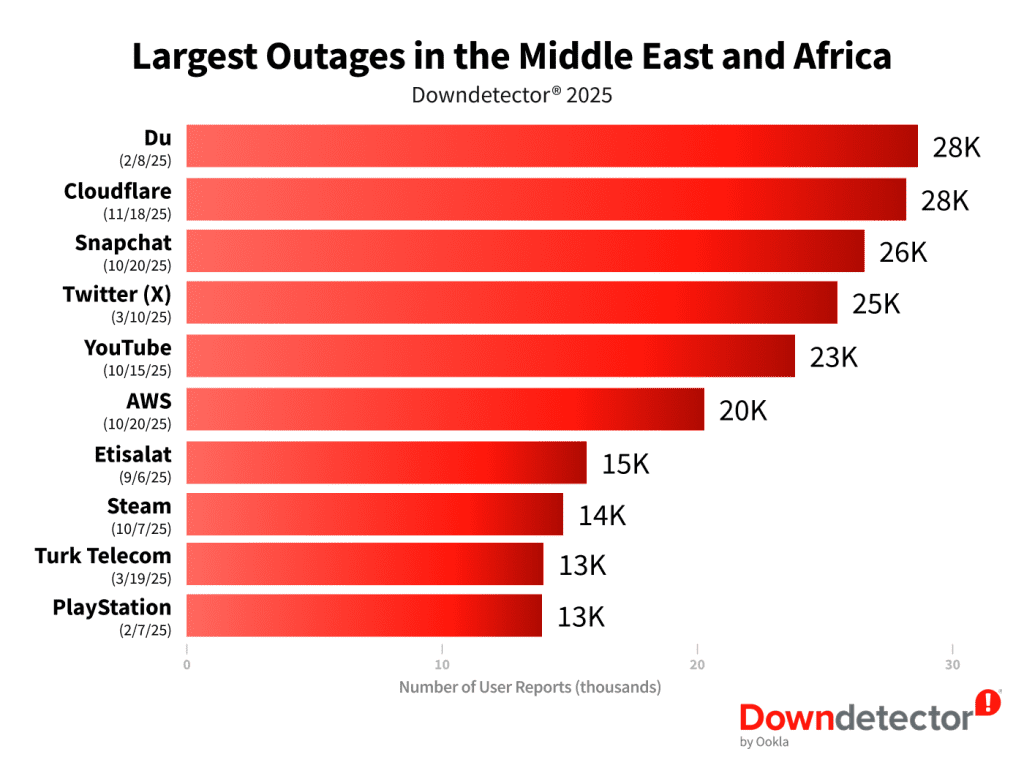

In the Middle East and Africa, the list is instructive. Du’s February disruption generated 28,444 reports, a reminder of how exposed users are when national connectivity leans heavily on a small number of operators. A global Cloudflare outage rippled through the region with 28,016 reports, while a Snapchat service disruption in October logged 26,392 reports. These aren’t niche platforms. They’re everyday utilities, relied on for communication, work, content, and commerce.

South Africa isn’t called out explicitly in the regional data, but the dynamics are familiar. Local networks sell resilience and redundancy, yet much of what South Africans rely on sits upstream, routed through global cloud providers and content delivery networks. When those systems fail, the effects land locally, regardless of how robust the last mile might be.

The global figures make that dependency harder to ignore. The single largest incident of 2025 was an AWS outage that triggered more than 17 million Downdetector reports across Amazon itself and the vast ecosystem of services built on top of it. This wasn’t one company going offline. It was online retail, internal business tools, media platforms, and customer-facing services all stalling together. The second-largest outage came from the gaming sector, with over 3.9 million reports tied to the PlayStation Network, followed by a global Cloudflare disruption that generated more than 3.3 million reports.

What these incidents have in common isn’t sector or geography, but concentration. A small number of platforms now sit so centrally in the internet’s architecture that when they stumble, failure becomes collective.

There’s a tendency in the industry to treat this as an acceptable trade-off. Centralisation brings efficiency, scale, and speed. But it also means redundancy is often more theoretical than real. Backups frequently live in the same cloud, rely on the same routing infrastructure, or depend on the same authentication layers. When something goes wrong at that level, there’s nowhere else to fall back to.

For South African businesses, this is where the conversation turns uncomfortable. What does resilience actually mean when your primary risk isn’t local infrastructure, but a hyperscaler halfway across the world? How much control do you really have when your uptime depends on systems you don’t operate and can’t influence? And who absorbs the reputational damage when customers don’t care that the outage wasn’t technically your fault?

This tension sits inside a broader local debate about connectivity itself. The issue isn’t simply whether people can get online, but who sets the terms, who carries the risk, and who absorbs the consequences when global systems falter and local users are left waiting. That imbalance becomes most visible not during periods of growth or investment, but during failure.

Ookla’s role in this ecosystem matters. As the company behind Speedtest and Downdetector, it both measures the internet and sells visibility into its weak points. Downdetector, including its business offering, doesn’t explain why something broke or who is at fault. It captures something simpler and often more useful: the moment users collectively notice that something no longer works. At scale, that friction becomes a signal, even if it lacks neat attribution.

The largest outages of 2025 don’t suggest the internet is about to collapse. Most of the time, it still works remarkably well. What they do show is that failure has become systemic rather than isolated. When things go wrong, they tend to go wrong everywhere at once.

For markets like South Africa, still negotiating questions of resilience, dependence, and control in a globally routed internet, that’s not just a technical concern. It’s a structural one, and it’s becoming harder to ignore.